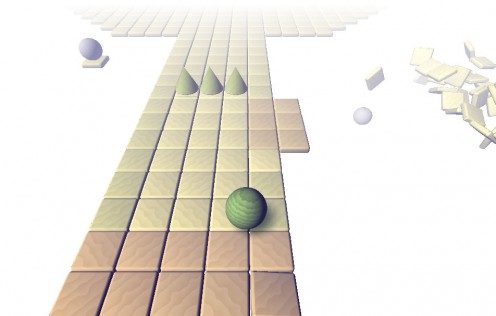

I actually spent a lot of time going back and forth on the colors. I wanted pastels; I wanted two colors that were contrasting, of course; I didn’t want your usual red vs. blue selection.

But most importantly, I didn’t want pink & blue. I didn’t want players to immediately see this boy/girl dichotomy there. Even in an abstract, hastily constructed game, I wanted to make sure I wasn’t reinforcing any of those save-the-princess type sentiments out there. It’s a pet cause of mine. So I went with green and a sort of bluish purple, which I figured were reasonably neutral colors.

Despite that, hearing people talk about the game, many referred to the purple ball as ‘she’ and the green one as ‘he’.

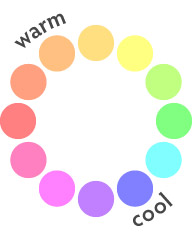

Trouble is, you’ve only got so many options. With sufficiently contrasty colors, one color is probably going to be warm — fiery reds and yellows — and the other bluer, cooler. In the absence of any other context, I suspect people are going to see the warm color as more feminine.

Near the end of the project, I worried that I was possibly falling into some gender stereotypes despite my best efforts to keep things neutral; the cool colored ball was the one you were controlling, the one with some agency; the warmer ball was completely passive, waiting to be rescued. I considered switching the colors, but didn’t have time to do it before the contest deadline came up.

But you know what? It wouldn’t have mattered. Because this is not about color choices or thinking that people who read too much into color choices are sexist. It’s about the biases we all carry.

Had I switched the colors, and had people read the purple player as female and the green object of its affection as male, you could say it was a gender-role reinforcing game design, to play a female character whose only goal is to find a mate.

Had I started with those colors — a purple player and a green companion — there’s a good chance I would have worried about that… and wanted to switch the colors.

Because I’m biased.

While I’d love the gender roles in the world to up and disappear, I certainly can’t say I believe they’ve already done so. I expect everything I see to express gender stereotypes; I expect to be annoyed by said stereotypes. Because I am biased, I will desperately try to pull my experiences in line with my expectations, spinning said experiences as needed. I will spin my perceptions of any game I play to fit in this world view, seeing sexism where there may be none — because thoughtless, sexist characterization is what I expect to see in most games.

And that applies to my perception of my own work. I will fight to keep my work egalitarian, but my biases will have me seeing depressingly overt sexism in everything I make. In a less abstract game, in a game with recognizable human characters, I will be wont to complain that I have failed to make such-and-such a female character sufficiently stereotype-breaking. I will graft a perception bias onto a character who may very well be, in an objective sense, portrayed in a perfectly respectful way. I will likely post a journal entry about it, wondering how I can do better. In my post, I will describe said character in terms of a stereotype that is an oversimplification of who the character actually is; and in doing so I will reinforce the very stereotypes I seek to avoid.

Fighting bias is a skill. Wanting to be less biased does not immediately grant you this skill. Wanting to produce works with an egalitarian world view does not immediately grant you this skill. I know I say that a lot, such-and-such-a-thing is a learnable skill, not a part of your core being. But having bias, being prejudiced or bigoted or whatever… it’s very, very tempting to think of acting upon bias as a failure of conscience, rather than a failure of skill.

I’m coming to the conclusion that it’s a lot more complicated than that.

I think it’s normal for people to project and interpret an artist’s creations according to what they know. We all have our biases.

You can *try* to put *your* preferred interpretation into their heads, but that’s never something guaranteed, and to some extent trying too hard to force people to think or respond a certain way feels oppressive. It’s better to welcome the audience and invite them to participate in the interpretation rather than hand them yours and tell them “This is how it’s gonna be.” They may all take it not the way you hoped, and that may be disappointing, but it shouldn’t be unexpected.

To some extent, it could be a failure to express yourself well (clearly and convincingly), or it may be that your ideas are just too new/foreign to your audience, or it may be that you’re working too hard against the grain.

That said, with your game I think you did as much as you reasonably could to lead people away from the cliched thinking that they used to interpret the game. I don’t think you’re at fault; I think it’s more just a matter of people falling back to cliched thought patterns when they encounter something new. That’s most people’s first response, and many people’s only response. Some people go further and explore their response and look for more. They try that cliche, whatever it is, on first, and see if it fits, and if it does, then most of them stop there. If it doesn’t, they often reject it, or if not, then it forces them to re-think and come up with new explanations. I think one of the most vital things about games is that they encourage us to come up with these new explanations and ways of thinking.