If there’s going to be action, I want it to be first-person action, and if it’s going to be first-person, there was this one niggling problem I wanted to solve, that pops up in every first-person game I’ve played: tunnel vision.

Humans have a nearly 180 degree field of vision horizontally. In contrast, a video game with a wide camera might give you 100 or 110 degrees, if I’m remembering things correctly.

I’d like to give you a wider field of vision than your typical game. If there’s a threat coming at you from the side, I want there to be a good chance that you’ll see it onscreen.

I’m shooting for 150 degrees here. So here’s a swiveling camera with a 150 degree field of view, and you can see why games generally don’t go this high.

There’s this really awkward pinching effect when you make standard video game cameras wide angle. Things on the edges look really distorted, and everything in the center looks farther away than it ought. This is what I’m trying to avoid.

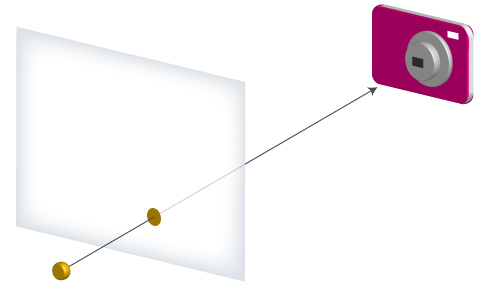

The animation above uses what’s called a planar projection. A projection is the process of taking your 3d game world and figuring out how to translate that to a 2d medium, your screen.

In this illustration, you’ve got a camera, a point in the 3d game world, and a 2d rectangle sitting a fixed distance from the camera, onto which the point is drawn. You draw a line from the point to the camera lens, and wherever that points intersects the rectangle, that’s where it will be on screen.

But this is just one kind of projection. You know how there are different map projections? Like the one where Greenland is way bigger than it should be, and the one that looks kinda like a banana peel? They all express the same thing, but try to reduce distortion in different ways. You can totally do the same thing with video games, though I’ve rarely, if ever, seen it done.

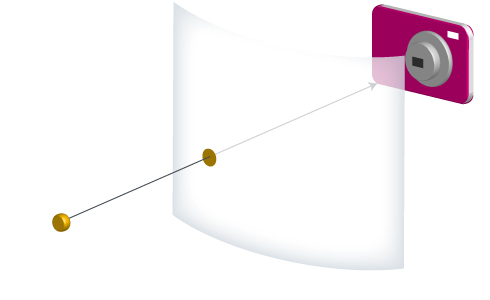

My first idea was to go with a cylindrical projection.

This time, the camera is in the center of a cylinder. You figure out where your point-lens line intersects the cylinder, and then unwrap part of the cylinder so it’s flat like your computer screen.

So that looks like this. Same camera position, same 150 degree horizontal field of view, same 180 degree swivel:

This removes the edge distortion. Completely. So completely, in fact, that it doesn’t even look like you’re turning anymore. It looks like there’s this flat image scrolling sideways across your flat screen. Which, basically, is what’s happening. You’re just unwrapping and flattening a different part of your cylinder.

This isn’t quite what I want either — a little bit of distortion can be an important visual cue that you’re turning around in a 3d world, and I want to preserve that.

So I went for a hybrid solution — something between a planar projection and a cylindrical one. There’s still a cylinder, but the camera isn’t in the center of it. It’s sort of like a flattened cylinder.

And that looks like this:

I’m really, really happy with this. I think I’ve struck a good balance here between reducing distortion and preserving the visual cues you get when you’re turning around.

That having been said, there are a couple possible issues here:

- This might cause some people to get motion sickness. Personally, I just don’t ever get motion sick, so I really don’t know.

- It’s a burden on the computer, to produce this effect. I’ve got seven cameras in my scene, all writing to a different part of the screen. That doesn’t make the frame rate a seventh of what it used to be — it’s more like, I dunno, two thirds — but it’s still noticeable.

- Also, since your field of view is wider, there’s more stuff to draw, further reducing the framerate.

I should probably just allow the user to set the field of view/ cylinderiness if they so wish.

* * *

So about that whole violence thing.

I’m not completely against violence in games. I’m ok with it if the violence is leveled against stylized spaceships or inanimate objects. And with the right approach, I’m willing to include violence in a more naturalistic setting:

- Your targets must not be living things, or sentient things like thinking humanoid robots.

- Winning a fight against a target must not have any intrinsic value, like showers of coins or experience points. The player must never be encouraged to pick a fight with a random bad guy because they’re behind on character advancement.

- Winning a fight against a target must not destroy the target. (It may, however, temporarily disable the target.) The player must never be encouraged to see eradication of all targets as the long-term solution to the threats the targets represent.

- To defeat a target permanently, the player must solve puzzles or do other non-violent things that cause the targets to do productive things instead of harmful things, or move them to a safe place.

- Each target must present a specific threat to your community, or the game world. Being a mortal threat to the player is not enough. Said threat must express itself in terms of real mechanics, like targets blocking a path, disabling a piece of equipment belonging to the good guys, or enabling the use of equipment belonging to the bad guys.

- Targets may never respawn unless it is made clear that respawning would naturally happen in a believable way in this universe.

Shooters are fun. Jumping on funny monsters and watching them fall off the screen in Super Mario Brothers is fun. Swinging your sword in Zelda is fun.

Point and click adventures are many things, but I’m not sure fun is one of them, generally speaking. And Tinselfly has mostly been defined as a high tech point and click adventure. I’ve been worrying about the fun factor.

I’ve been asking myself, can I have fun, action-based — dare I say it, violence-based — gameplay in Tinselfly that follows these rules above? And I think I found my solution within the TV show Supernatural.

* * *

Supernatural has this character Dean who’s a badass, shotgun-toting, Impala-driving, bacon cheeseburger devouring action hero who goes around ridding the world of nasty ghosts, among other things.

Here’s the deal:

Dean looks badass.

He carries guns.

He shoots ghosts.

He eventually defeats the ghosts, sending them to the afterlife where they belong.

And… Shooting the ghosts can never defeat them.

Now, Dean is not above outright murdering evil people if he thinks it’s for the greater good. But I just want to focus on the ghosts. Dean looks like a violent action hero, but the manner in which ghosts are defeated in his universe is (arguably) non-violent. To defeat a ghost, you have to find the bones of the dead person the ghost came from, and burn the bones. This usually involves lots of research trying to figure out who the ghost is, where they’re buried, who might have stolen the bones if the bones aren’t where they’re supposed to be, etc.

Research.

But, ya know, badass research.

The shotgun Dean carries around is loaded with salt. In this universe, throwing salt at a ghost causes it to disappear temporarily and stop bugging you — but the ghost will come back after being salted. A shotgun just delivers salt in an amusingly badass way.

And it works. I’m seven seasons into this show and just now realized that Dean is a shotgun-toting, ghost-destroying badass who doesn’t dispatch a single ghost with his shotgun. The shotgun is an affectation.

* * *

So I can give Robin a sword. She can temporarily disable mechanical baddies by destroying their shields, as described here. She can solve puzzles trying to figure out what’s controlling the baddies, and re-purpose them or send them to safe places where they will do no harm. Her mental state can affect her fighting, so this can mesh with the character-driven puzzles I want to include as well. And her fighting can affect her mental state, which could lead to more interesting character development.

Robin can look and feel like a sword-swinging badass, without ever running anyone through. And I think this can work, and I’m comfortable with this approach.

Gotta go design and model a mechanical baddie now.