(Spoilers on both movies ahead.)

The other night, I saw the new Battleship movie. And, surprisingly enough, I kept comparing it to the latest Star Trek movie.

Star Trek was critically acclaimed. Battleship was universally panned. But they have lots of similarities:

- We start with a protagonist who’s a bit of a screwball.

- Said protagonist demonstrates his screwballness in a scene involving him in a bar trying to impress a girl he just met, and instead getting into trouble.

- Protagonist gets a chewing out by someone in the military, is told that they have lots of wasted potential, and is urged to join the military.

- Protagonist joins the military.

- Protagonist develops a rival within the military, a person somewhat more by-the-book than himself.

- Bad aliens attack. Good guys don’t fare so well.

- Protagonist demonstrates his ability to command a ship in a pivotal scene involving his rival.

- Good guys defeat aliens.

Now, admittedly, there’s a lot more to Star Trek than this possibly pedestrian screwball-does-good character arc, which has been done many times before. And the constraints that movie had to deal with, what with rebooting the franchise and all must have been crushing for anyone involved, But to the extent that I rather like pedestrian character arcs, and am going to focus on that aspect of any movie that has one, I kinda liked Battleship better than Star Trek.

exposition

Let’s start with the screwball. Star Trek’s Kirk gets in a bar fight while hitting on a girl who’d just as soon be left alone. There are nice moments, but it’s not that memorable a scene.

In contrast, Battleship’s Hopper is introduced in one of the funniest scenes in a movie I’ve seen in a while. Here, he girl wants something: a chicken burrito. The bar’s not serving food anymore, so our protagonist, in a desperate attempt to be helpful, runs to the nearest quickie mart to get a burrito. The mart is closed, so he breaks in, warms up a burrito, leaves some money on the counter, makes a huge mess of the place, gets chased by cops and gets tased just after delivering said burrito, falling unconscious at the feet of the girl he’s trying to impress.

It’s absurd, it’s funny, it’s memorable, and it’s strangely endearing. I’d go so far as to say it’s the best introduction of a screwball character I’ve seen.

the set-up

The next few scenes have one of those things where an unfortunate chain of events forces our unprepared, screwball hero into a situation where he suddenly has to prove his worth as a leader.

The captain of Kirk’s ship has to go do some super-dangerous stuff, leaves Kirk’s rival in command, and much to everybody’s surprise, makes Kirk the new second in command.

In contrast, in Battleship, the entire command staff of Hopper’s ship is killed, leaving Hopper as the senior ranking officer. Structurally, I like this set-up a little better. Hopper is completely blindsided by this. He goes from zero to captain in a single scene. We’re shown Hopper’s lack of fitness as a leader because he’s a really bad captain at first. He doesn’t have the trust of his crew at all, but he’s still captain and has to figure out what to do.

Kirk, as second in command, has to prove he’s better than his rival before he can take command and actually make command decisions. We don’t necessarily get a great sense of how exactly Kirk’s loose-cannon-ness might make him a bad captain and why nobody trusts him.

baggage

Both Hopper and Kirk have relatives in the military who die in combat early in the film, and Hopper and Kirk want to live up to these shining examples of military officers.

Kirk’s baggage is his father, who died saving a just-being-born Kirk. It’s noble and all, but you can’t really say Kirk and his father had an interesting relationship.

Hopper’s baggage is his brother, who he lived with well into adulthood, and who he works with in the Navy. We see them talking; we see Hopper’s brother trying to take care of him; we see the brother’s disappointment when things go badly. That relationship is the core of the first few scenes of the movie.

pay off

So finally we have our scene where our hero rises to the occasion and becomes the leader he needs to be, for the world to be saved.

Kirk does it by tearing down his rival. By proving that his rival, the current captain, is emotionally unfit for command.

A rival whose entire home planet just got swallowed by a black hole.

I find that pay off more than a little anticlimactic. If your home planet just got erased form existence, you might be a bad captain for a while, too.

In Battleship, Hopper proves his fitness by temporarily letting his rival run the ship, because his rival has come up with a brilliant plan for defeating the aliens. Hopper proves his fitness by acknowledging that command isn’t about doing everything yourself; it’s about understanding the strengths of your crew and managing them well.

On an emotional level, I actually found this surprisingly satisfying. That arc really worked for me.

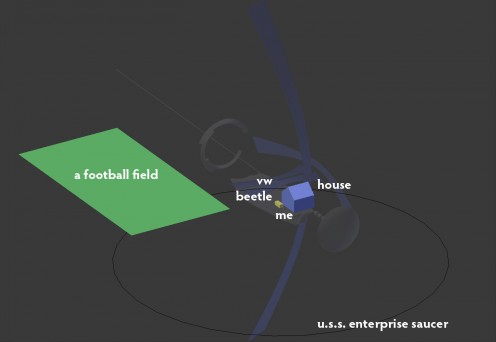

set piece

On a completely non-character-driven level, I liked the action scenes in Battleship more than Star Trek too. Being based on a board game, everything’s a bit more, shall we say, rules heavy. And I think any good set piece should have rules. Some people might groan at Hopper’s rival’s plan to chart the course of the aliens on a giant grid with letters on one axis and numbers on the other, but I rather liked that. It was better than watching starships flying at each other with guns blazing. There’s no structure to that.

And I rather like silly, overly abstract structures overlaid on my movies, whether you’re talking about set pieces or character development.