* * *

For a brief period in high school, I regularly had three dance classes in one day. At the time, and up until just now, I focused on the time I was putting into it: an estimated 14 hours a week. It was a pretty decent chunk of time.

But looking back on it, the number isn’t the only thing that’s important. The other important thing was that I had three separate and distinct dance-related activities.

Every morning I had a class on technique. Every afternoon was spent rehearsing pieces for an upcoming show. And frequently, between classes, I’d run off to the studio to work on choreographing and practicing a solo piece.

And in each of these three activities, my mindset was different. Sometimes I was focused on being creative; sometimes I was not. Sometimes I was trying to stay in sync with my classmates; sometimes it was just me, learning to keep an eye on myself in the dance studio mirrors; sometimes I wasn’t looking at anything at all, trying to develop a good sense of balance and positional awareness. There was a specific time for each little thing I needed to learn, to get better at what I did. And while I wouldn’t say I ever got to be a great dancer, having those things separated out, was, in hindsight, a great thing to have happen.

* * *

In an attempt to improve my skills and efficiency in, well, pretty much every creative thing I do, I am going to try integrating small-scale game-making exercises into my regular project rotation. It’s kind of like a different classroom environment. I’ve always been a fan of having multiple projects at once so they can kind of creatively feed on each other, but I don’t think I’ve specifically drawn a line before and said, these things are for production; these things are for learning. I want to make sure I spend time in both mindsets, and really commit to one or the other when I’m working so I can learn more about whatever I’m working on.

* * *

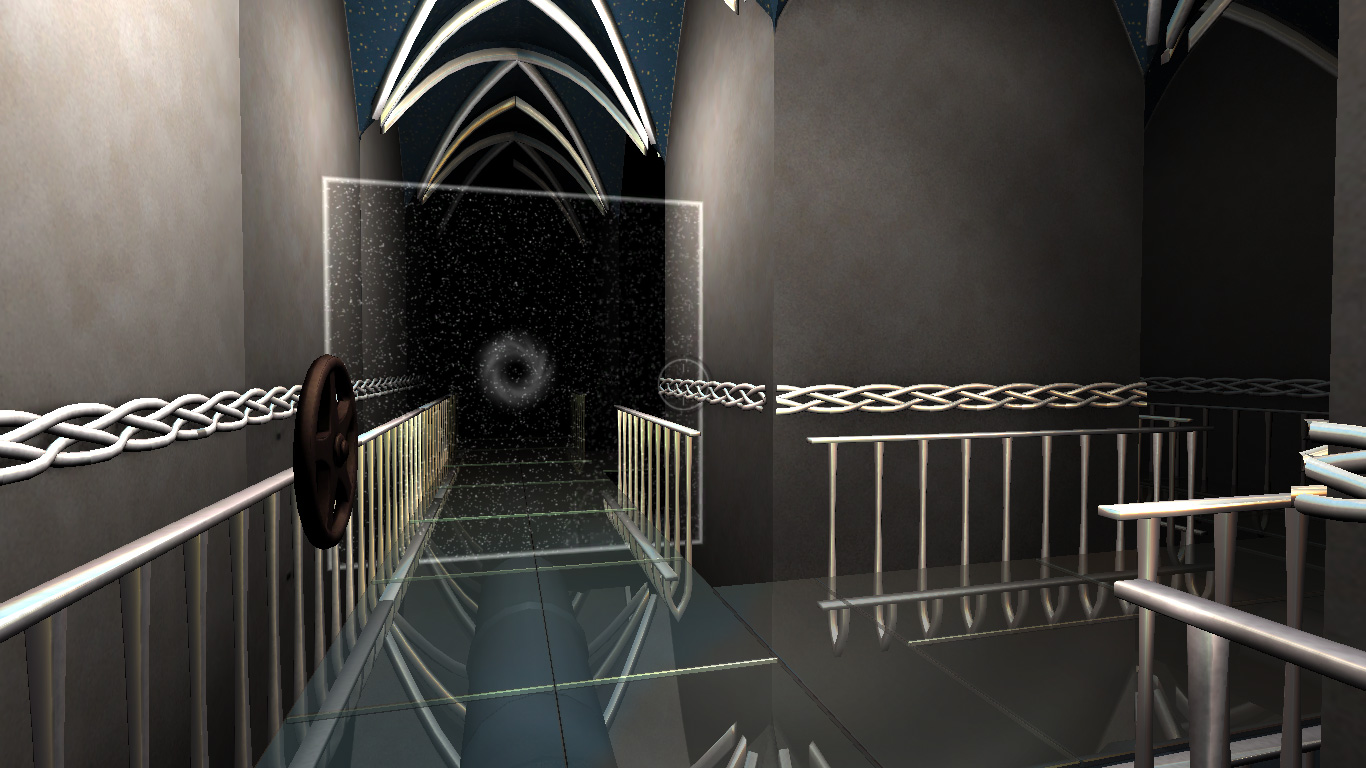

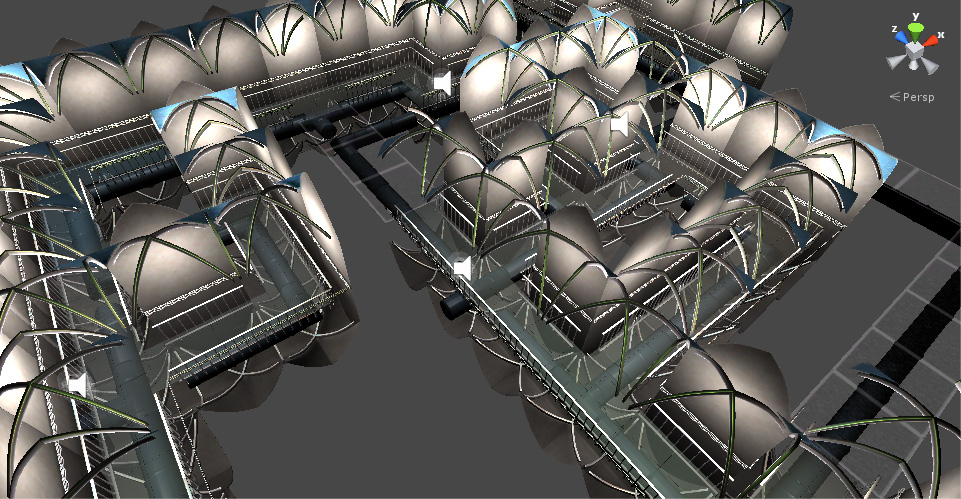

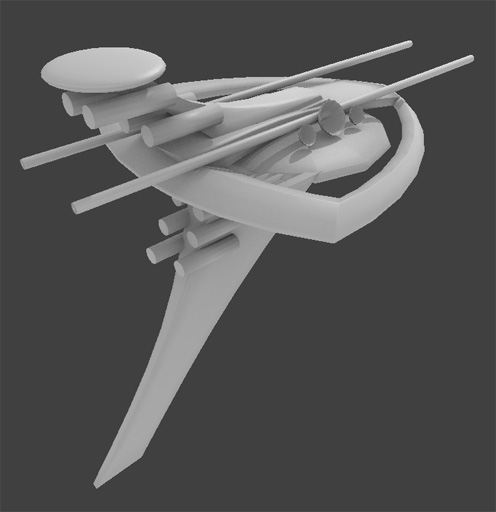

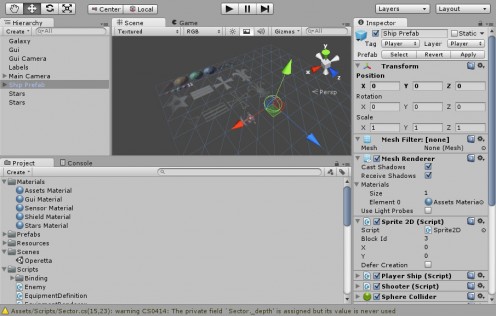

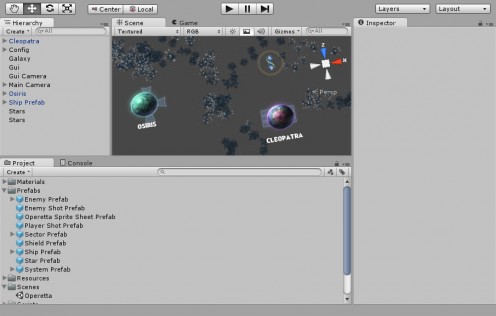

My first assignment is an arcade-style thing meant to teach me about level design. My second, which I’m working on at the same time, is a spaceship flight sim where the emphasis will be on modeling and making responsive, natural-feeling player controls. I’m afraid I don’t have much to say about the former right now, but in regards to the latter, I learned a little bit more about how to make low-polygon meshes this week.

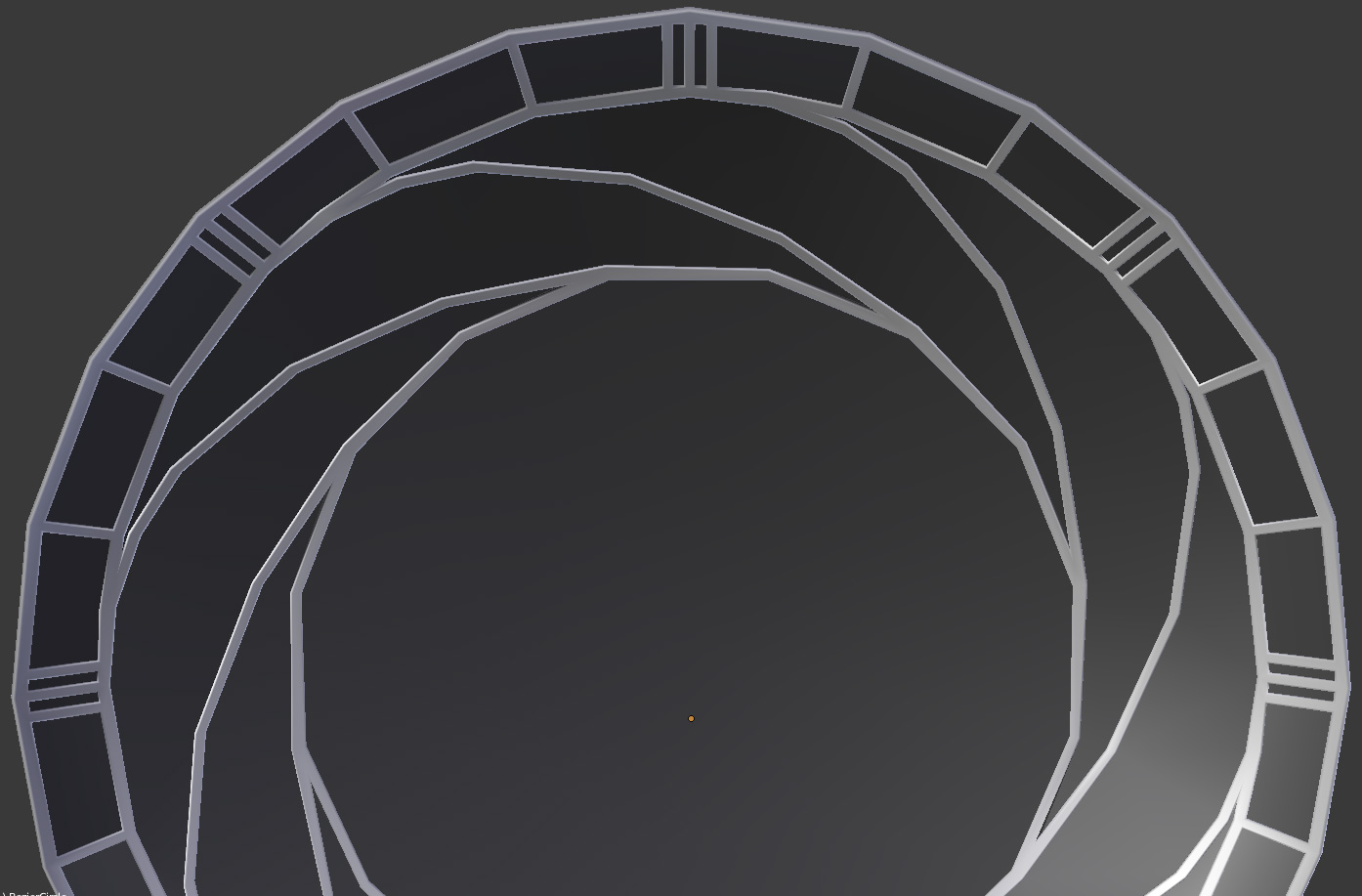

My first job is to model a spaceship cockpit. Right now, it looks vaguely Star Wars-y: there’s a big, round window with a decorative grill.

And here’s what I’ve learned the hard way: making a low-polygon mesh is not about making a high-polygon mesh and then simplifying it. You have to think in terms of the simplified version before you even start modeling.

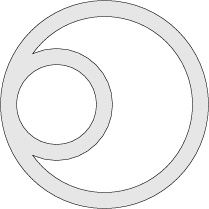

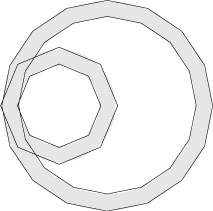

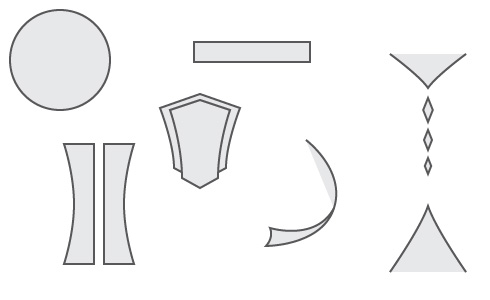

I’ll explain that by way of a simplified example. Suppose you want to model this:

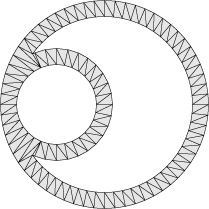

If you want to use this shape in a video game, you have to turn it into something a video game understands: a mesh made of triangles. Like so:

While each triangle has perfectly flat sides, the appearance of curves can be simulated by using very small triangles. When you use enough small triangles, you get the appearance of smooth curves.

Unfortunately, more triangles frequently means slower games. It’s not the only thing that can affect the performance of a game, but it is something you need to worry about. And I always start off by making meshes with too many triangles.

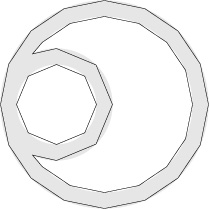

The obvious solution here is to take the high-resolution mesh and systematically remove detail from it. Here, I’m using a subset of the points used in the detailed mesh.

Check out the area where the small circle meets the big circle — there’s a sort of Y intersection there. And in this mesh, the widths of the strokes all around that Y feel totally wrong. And the inner circle is a little thinner than the outer one.

What’s happening here is that I’m reducing the number of triangles in the mesh without any real awareness of or respect for when the mesh actually represents. I’m treating this as a series of outlines, like so:

The relationships between each of those shapes is getting totally lost. What’s really happening here, of course, is that I have two outlined circles that need to feel circular in the final product.

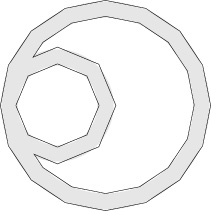

I need to not reduce the triangle count the intersection of the two circle outlines. I need to reduce the triangles in the individual parts of my mesh —

— and then combine the derezzed versions.

Now, that Y intersection where the small circle meets the big one looks much better.

I’ve also made a change to how the simplification of the circles happened here.

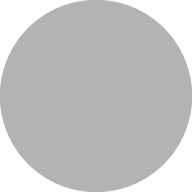

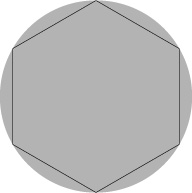

If I have this circle:

And this overly-detailed mesh:

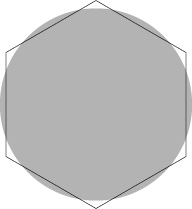

And then systematically remove points on my mesh, I get this–

–I get a shape inscribed within my original, a shape which is much too small to be an accurate interpretation of the original.

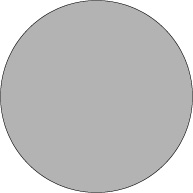

The new mesh should have around the same area as the old one. Like this:

Note that the vertices of the hexagon here aren’t on the circle. My simplified mesh doesn’t actually contain any of the points on the old mesh.

* * *

Of course, it probably wouldn’t be that useful to model individual parts of something and then use your modeling program’s boolean tools to combine them. Rather, the thing I’ve learned here is that I should start thinking in terms of a simplified mesh earlier, and model that–rather than modeling something that’s too detailed, and then programatically simplifying the detailed version (whether it’s an actual simplification utility in your app, or just thinking too programmatically).